WB-47E

|

| Atlanta Journal and Constitution Photo

by Floyd Jillson |

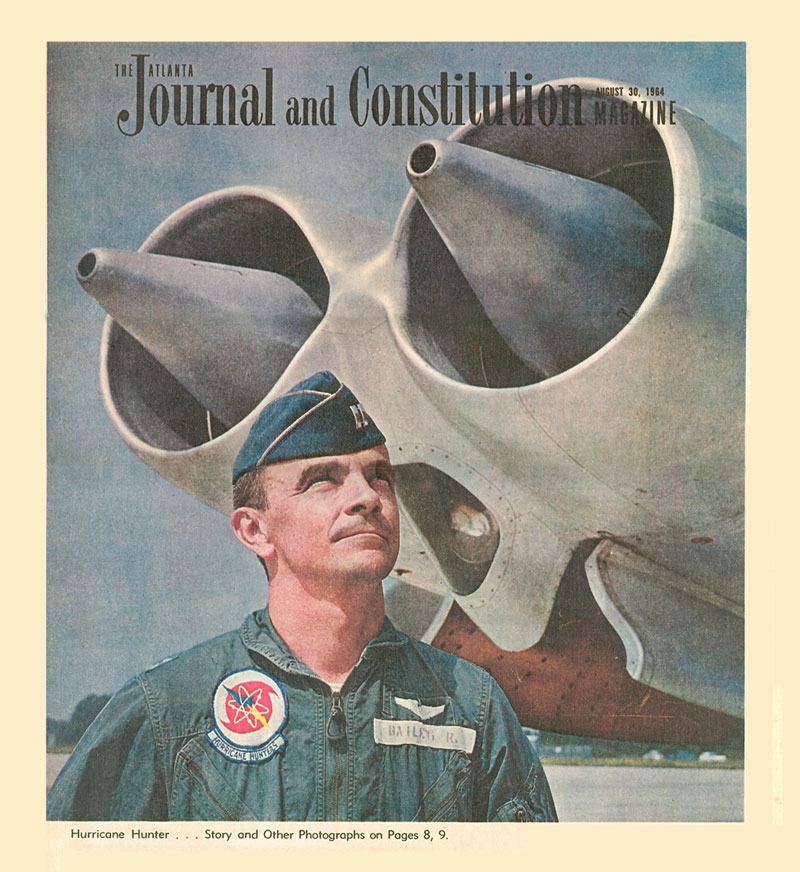

| There

was much fanfare in late 1963 through the summer of 1964 over the

arrival of the newest member of the weather reconnaissance family - the

WB-47E. Thirty four of the jet aircraft had been delivered to Air

Weather Service squadrons in California, Georgia, Guam, and Japan; as

well as to a detachment in Alaska. One example of this attention comes from the Atlanta Journal and Constitution Magazine of August 30, 1964. This weekend insert had full page cover showing Captain Robert Bailey of the 53rd WRS standing in front of the No. 4 and 5 engines of WB-47E tail number 51-2366. Captain Bailey, along with Major Dale Sutherland and Captain David McGrath, were preparing for a flight described by the article's author as a Hurricane Patrol. The two page spread inside the magazine (plus two more pages of text) was titled "Hurricane Hunters of Hunter." It talked about the 53rd WRS transition from the WB-50D to the new WB-47E, and its move from Kindley AFB, Bermuda, to their new home at Hunter AFB in Savannah, Georgia. |

1. The WB-47E Aircraft

|

| Official Lockheed Photo, Courtesy of Air Force Weather History Office |

| The

"new" weather reconnaissance aircraft had been SAC B-47E's that were

scheduled for retirement. The contract to refit them fell to the

Lockheed facility in Marietta GA. In the photo above, we see Pat

Rainwater, Miss Lockheed-Georgia, standing next to the U-1 air sampling

foils mounted on the forward bomb bay doors of a WB-47E. The U-1

foils (for collecting particulate debris from nuclear tests) made up

just part of the atmospheric sampling suite. The photo was taken in 1963 at the Lockheed-Georgia plant in Marietta, GA, shortly after the first ex-SAC B-47 had completed modification and was cleared for its acceptance flight. The WB-47E could carry two foils as shown, but normally flew with just one. One of the main goals of the refit was to reduce the operating weight of the air frame. Every possible step was taken to lighten the load. The defensive systems (tail guns, aiming radar, etc.), bombing systems, even the air refueling plumbing and external tanks were removed. The resulting weather aircraft weighs in at 174,000 lbs at takeoff, compared to as much as 230,000 lbs for the SAC version of the E-model. WB-47E had an unrefueled range over 2,800 miles, enough to fly all of the existing fixed weather tracks - in half the time of the WB-50D that it replaced. The six-jet aircraft also could fly as high as 40,000 feet (above 200 millibars) whereas the WB-50D usually operated at 18,000 ft (500 mb) or below. Before we leave Miss Lockheed-Georgia, note the faring mounted in the bomb bay doors to accept the U-1 foil. The U-1 was first installed in the five WC-130B aircraft that had been delivered to AWS in 1962. The mounting plate for the U-1 was molded to match the curvature of the WC-130B forward fuselage. Both the WB-47E, and later WC-135B, had to be modified to match the perfect WC-130 form. (Guess which aircraft the author flew? Yes, it was the WC-130.) |

SPECIFICATIONS:

|

2. WB-47E Weather

Reconnaissance and Atmospheric Sampling Systems

| Illustration from Boeing's B-47 Stratojet by

Alwyn T. Lloyd |

|

|

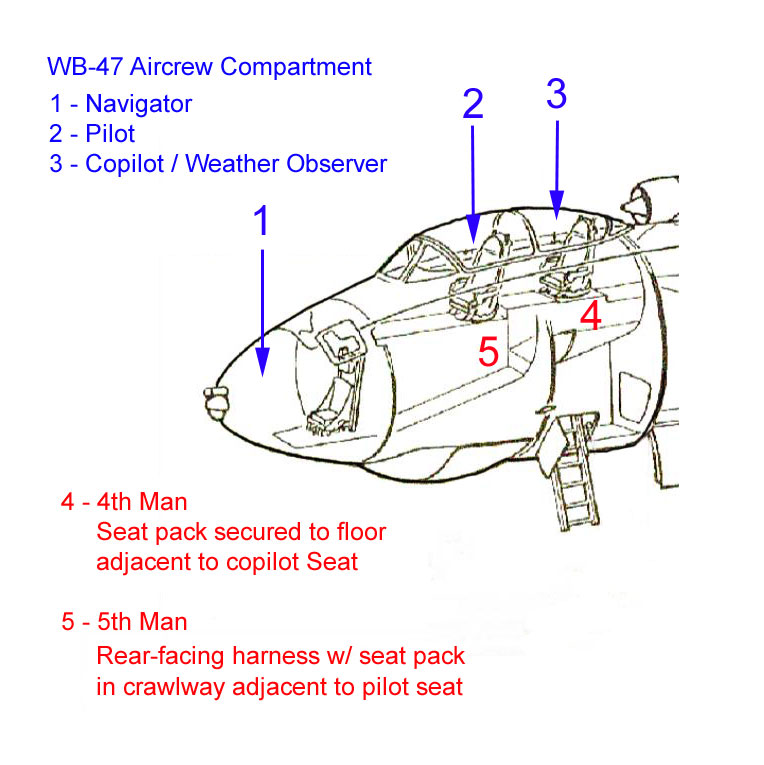

| The

WB-47E had one immediate difference from the WB-50D. Designed for

a 3-man crew, there was no provision for either a weather officer, or

for a dropsonde operator. The highly sophisticated (for its time)

AN/AMQ-19 MET system was intended to do most of the meteorological

function automatically. Both the horizontal data, and vertical

data from the dropsonde system, were to be taken and recorded by the

computers, and then transmitted to waiting ground stations. The

operating controls for the AN/AMQ-19 were located on the aft panel at

the copilot's station. The copilot could rotate his seat to

operate the MET gear and transmit the data. The WB-47 pilot

crew members received some additional weather training to help in their

new role. The vertical system centered around a 9-shot revolver dispenser for dropsondes. These were pre- loaded by the MET/ARE folks prior to takeoff and there was no provision to reload in-flight. Like the horizontal data, information from the falling dropsonde was recorded on-board the WB-47, and transmitted to the ground station in raw form. Processing and quality control that had previously been accomplished by on-board dropsonde operators was now done on the ground. |

|

|

| Illustration

from Boeing's B-47 Stratojet

by Alwyn T. Lloyd |

|

|

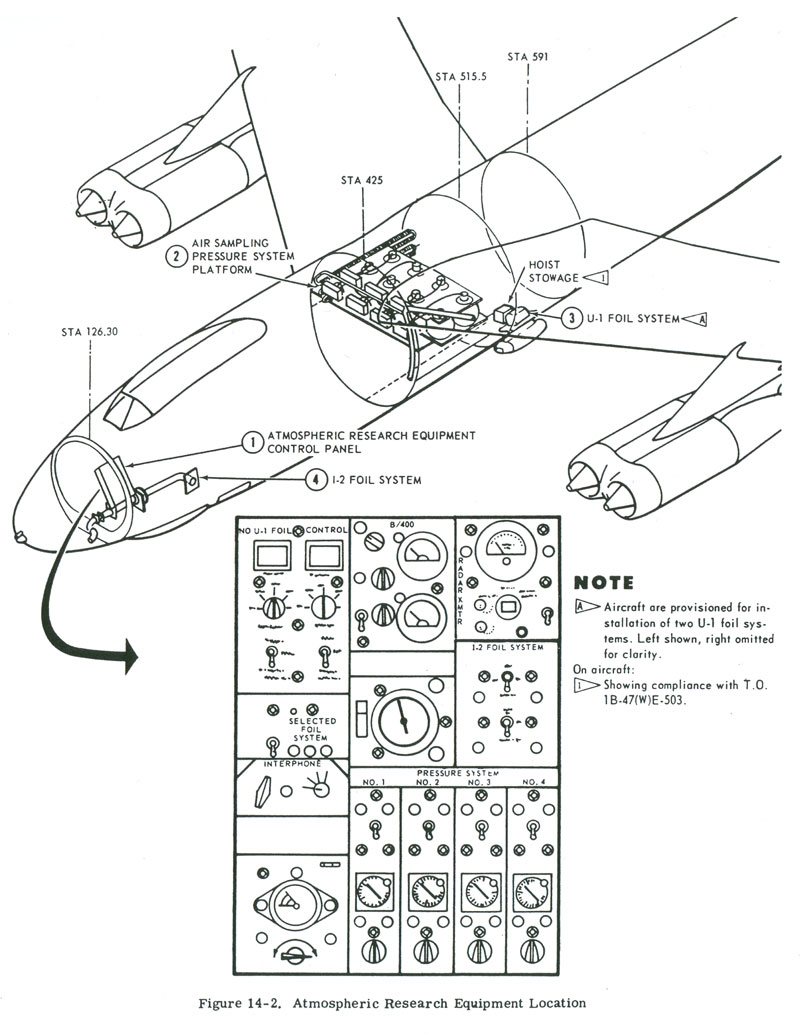

| The

publicity surrounding the arrival of the WB-47E made almost no mention

of the atmospheric sampling equipment. The role of weather

reconnaissance as a key component of the US Atomic Energy Detection

System (AEDS) was a very closely guarded secret until the late

1970's. When sampling aspects of our missions were discussed, it

usually centered on support to domestic (US) testing, such as the

Dominic series of nuclear tests in 1962. AWS had been named

single manager for atmospheric sampling in 1961. As part of that

designation, AWS assumed control of the RB-57 mission at

Kirtland. They did not get control of any SAC assets. Both

B-52 and U-2's were capable of carrying ARE, but remained under SAC

operational control. The WC-130B and WB-47E were intended to

upgrade the Long Range Detection (LRD) capability of the USAF and AWS. In reality, the atmospheric sampling ability of the WB-47E had been the primary driver behind its acquisition by AWS. The range and speed of the B-47 meant that all of the tracks designed to intercept air masses originating over Soviet test sites could be flown quickly, and the whole air and particulate samples could be returned to the laboratory in a very timely manner. The promise of a near 100% guarantee that the intelligence system would detect Soviet violations was key to the US Senate ratification of the 1963 (and later 1973) Limited Test Ban Treaty. WB-47's would also play a major role with Joint Task Force 8 (JTF-8) annual readiness exercises. JTF-8 was tasked to maintain the ability to rapidly resume atmospheric nuclear testing if the Soviets were caught cheating. The US nuclear testing system was caught totally unprepared in 1961 when the Russians broke the informal moratorium on above-ground testing. It had taken almost a year to resume testing and JTF-8 was to make sure the US was ready to respond if the treaty was violated. On the WB-47E, the ARE was operated from a panel located on the left side of the fuselage just aft of the navigator. Again, the plan was for the navigator to change filter papers in the U-1 foil (using the record changer-like closed system) and start pumping whole air into the pressure platform bottles. Often, a fourth crew member, a Special Equipment Operator (SEO), came along to operate the ARE. The SEO's were assigned to units belonging to the Air Force Technical Applications Center (AFTAC). This procedure was used on the daily Ptarmigan missions from Eielson AFB that went towards the North Pole and then returned to Eielson. |

3. Where the WB-47E Was Based

|

|

| Official

USAF Photo, Courtesy of Air Force Weather History Office |

|

|

| The

first production WB-47E was accepted by Lt Col Robert V. McKibban,

commander of the 55th WRS, on 24 May 1963. The prototype E-model

had been delivered to McClellan

in March 1963, joining the only WB-47B weather bird. The 55th was

to receive the first 15 (of 34 planned) aircraft. Also getting

the converted jet bombers in 1963 were the 53rd WRS "Hurricane Hunters" at Hunter AFB, GA; the 54th WRS "Typhoon Chasers" at Anderson AFB, Guam; the 56th

WRS at Yokota AB, Japan;

and Det 1, 55th WRS at Eielson

AFB, AK. By 15 November 1963, all 34 aircraft had been

delivered to AWS. In 1965, AWS started receiving additional modern aircraft. The turbofan powered WC-135B was destined to become the premier atmospheric sampler, and in fact two upgraded versions of the 135 continue supporting this national mission today. There were 10 of these WC-135B's assigned in 1965, with 5 each at the 55th (McClellan) and the 56th (Yokota). In addition to the ARE gear, the WC-135B had AN/AMQ-25 MET system. Using the latest IBM technology, it was the next generation after the AN/AMQ-19 from the WB-47E. The WC-135 also had the advantage of being able to carry many additional crew members. A dedicated weather officer, dropsonde operator, and two Special Equipment Operators routinely joined the 2 pilots, navigator and flight engineer. The WC-135 could also carry augmenting pilots and navigators for extended duration missions. The 5 WC-130B's were originally configured in 1962 as dedicated samplers (ARE only). In 1965, they were upgraded with a complete MET system, and joined by 6 WC-130E aircraft with both MET and ARE. The WC-130B's were sent to Ramey AFB, Puerto Rico, as Det 2, 53rd WRS. The WC-130E went to the 54th WRS at Andersen AFB, Guam. They quickly became the primary hurricane and typhoon reconnaissance platforms. These additions caused a ripple effect in the weather reconnaissance world. In Sep 1965, the 57th WRS moved from Avalon, Australia to Hickam AFB, HI. In Australia, the 57th had flown RB-57 aircraft acquired when AWS assumed sole sampling management. Once in Hawaii, the 57th would have only the WB-47E. These aircraft came from the 54th WRS, which now flew only WC-130 types, and the 56th WRS, now equipped with the WC-135B and R/WB-57F. Actual tail numbers rotated between the various WB-47 units to average out the flying time and sortie rates. In Jun 1966, the headquarters of the 53rd WRS moved, along with their WB-47's, from Hunter AFB to Ramey AFB, Puerto Rico. The separate Det 2, 53rd WRS was disbanded. On 8 July 1966, Det 2, 57th WRS was established at Clark AB, P.I. with 4 WB-47E assigned. The first detachment commander was current AWRA Board Member, Lt Col John H. Hug. Det 2 averaged 2 missions a day over the next 3+ years in support of SAC B-52 missions in SEA. In 1968, the Detachment at Clark AB was redesignated Det 2, 9th WRW. Det 2 had as many as 7 WB-47E assigned at any one time. Over time, the WB-47E fleet stabilized at 24 UE aircraft worldwide, plus 4 backup aircraft. Most people realized that the aging WB-47 was vulnerable to budget cuts. Having said that, the weather community was still taken by surprise when, on 25 Aug 1969, the Air Weather Service commander announced that the WB-47E fleet would be immediately retired to help meet a $1 Billion reduction in the FY70 USAF budget. By 30 Oct 1969, all remaining WB-47's were flown to Davis-Monthan or transferred to various organizations for future display. The 57th WRS at Hickam, and Det 2, 9th WRW at Clark were officially disbanded in Nov 1969. |

4. WB-47E Missions

|

|

| Official

USAF Photo, Courtesy of Air Force Weather History Office |

|

|

| Hurricane and Typhoon Reconnaissance As noted at the beginning of the article, the early press coverage emphasized the role the WB-47E would play in replacing the WB-50D tropical cyclone reconnaissance. It was also made clear that the B-47 would not penetrate the storms at 700 mb (10,000 ft) as had been the case previously. The B-47's would fly over, and around, the storm at high altitude, gathering data with the MET system, and using radar to track the storms location. Today, NOAA Gulfstream IV aircraft perform similar functions. The advantages cited for the B-47 type was its speed in reaching suspect areas and the monetary savings of a smaller crew, etc. Unfortunately, the technology of the 1960's was not quite there yet. The limitations of the AN/AMQ-19 were very apparent to the forecasters of the National Hurricane Center and the Joint Typhoon Warning Center. Both the Department of Commerce and PACAF insisted that WB-50D continue to provide primary data using the 700 mb penetration method until the WC-130 could be fielded as a replacement in 1965. The only WB-50D unit left in 1964 was the 56th WRS at Yokota. The 56th was tasked to send 3 aircraft and crews to the 53rd at Hunter for the 1964 hurricane season, as well as continue to support typhoon reconnaissance in the western Pacific. Despite the limitations, the WB-47E crews continued to fly their high altitude hurricane missions in the Atlantic and over the Eastern Pacific (off the Mexico coast) throughout their time in AWS. John Hug remembered one of his his career highlight missions flown with the 53rd WRS. Tasked for a night hurricane "penetration", if possible, John flew directly over the hurricane at 39,000 ft (200 mb). He was required to remain under visual conditions. There was a bright moon that night, and the perfect stadium eye wall opened below them all the way to the surface, where the moon reflected off of the ocean below. He can still picture the scene as if it were yesterday. Standard Synoptic Weather Tracks The majority of hours and missions of the WB-47E were flown on standard weather tracks from the far flung bases. These bread-and-butter tracks, named after various birds, provided much needed filler data to the budding AF Global Weather Central computers. The Atlantic tracks of the 53rd WRS were named Gull. The 55th WRS tracks to Hawaii, Alaska, or round-robin to McClellan were called Lark. Det 1 in Alaska had the Ptarmigan (later changed to Stork) mission that went over the Arctic Ocean towards the North Pole, as well as the Loon tracks across the Bearing Sea and west to Japan, and the Loon Alpha, that went south through the Gulf of Alaska to Hawaii. The 56th WRS had Buzzard tracks. They were renamed Robin at the same time that the Ptarmigan was changed. The new air traffic computers had to have call signs with no more that 7 characters, which limited the name to 5 letters. On Guam the Vulture routes became Swan, but these were rarely flown by the WB-47 after the 54th conversion to the WC-130E in 1965. The 57th in Hawaii had the Petrel missions that went south towards the Equator and north into the Gulf of Alaska. Depending on location, the crews would often "drag papers" on these tracks, i.e. change filter papers on the U-1 foil at regular intervals, and pump whole air samples into the bottles of the pressure platform as tasked by AFTAC. JTF-8 Readiness Exercises Described under the ARE information (see Section 2). ARCLIGHT Flown by WB-47E of Det 2, 57th WRS (later Det 2, 9th WRW) from Clark AB. The missions flew along planned refueling areas to be used by B-52's returning to Guam from SEA bombing missions. The WB-47 crews identified the best areas, looking for regions with no turbulence and lots of visibility. Similar to missions flown ahead of fighter movements, except that they were in the same geographical area every day for 3+ years. Systems Command Generally flown out of Hawaii. These missions were later called Cold Miss. They supported USAF Systems Command efforts of recover the capsules ejected by Corona spy satellites. Weather tracks criss-crossed the planned recovery zone, observing cloud layers, visibility, and turbulence, reporting anything that might interfere with the 6594th Test Group recovery efforts. TAC Support Also referred to by various Coronet names or Exercise names. The WB-47E flew the planned refueling areas for fighter deployments. Data from the weather crew might be used to alter the air refueling plan by changing altitude and moving an A/R track. If the weather was bad enough, the deployment might be postponed. Over the years, information from the missions saved many a fighter from diverting because they could not take on fuel, or even the potential loss of an aircraft. Special Sampling Missions Tasked by AFTAC, these missions were very similar to the daily synoptic tracks flown out of Alaska, Japan, Hawaii, etc. Just like on the synoptic track, the navigator, or SEO, if present, would change filter papers on the U-1 foil at regular intervals, plus start and stop pumping air into the pressure platform bottles. The difference was that the mission was looking for a specific debris field from a previously detected Soviet test. Even underground testing tended to "vent" (especially Soviet tests) and our crews were looking to collect evidence that the cloud was allowed to cross out of the Soviet Union, in violation of treaty commitments. The samples collected could also be used to judge the specific purpose of the testing and the internal design of the weapon. If the crew received indication of an "in flight positive" on the B-400 rate meter, they would attempt to orbit within the debris cloud for as long as possible, thus giving the best sample to the lab. Various Research and Test Programs Missions such as Sonic Boom, BOMEX, Cold Cut, Cold Bounce, etc. were used to study specific meteorological events. Missions were normally of limited scope. Often the WB-47E participation was strictly for general area reconnaissance of weather conditions. They also served as "ground truth" for validating early weather satellites. Data collected by the satellite analysts was compared to that observed directly by the WB-47E systems. These are not the only missions flow by the WB-47E, but give a good flavor of what they contributed during their six year history. |

5. WB-47E Accidents and

Incidents

|

|

| Photo Copyright by John

Shampnoi. All Rights Reserved. Used with Permission. |

|

|

|

| Photo Copyright by John

Shampnoi. All Rights Reserved. Used with Permission. |

|

|

| 51-7049 / 21 April 1964 / 55th WRS /

Eielson AFB, AK Barely six months after the first operational missions flown by WB-47E aircraft, the only accident occurred that resulted in fatalities. A three man crew from McClellan was TDY to Eielson to fly on the Ptarmigan polar track. Since this was the first Ptarmigan mission for the 55th navigator, Capt Warren S. Hillis, a Det 1 Instructor Nav was on board to check out Capt Hillis on polar procedures. This duty fell to Maj Conrad L Leinhart. Also on board was TSgt Charles F Heckman, an AFTAC SEO. Three men downstairs made for cramped quarters. Then Capt Dick Purdum was assigned to Det 1 at that time, and flew on another mission that day. Dick would later serve as the Standardization Pilot for the WB-47 at the 9th WRW. As Dick relays the story, the mishap aircraft commander was then Maj Franklin Ross. Due to his unfamiliarity with the Eielson runway, being stationed at McClellan, Maj Ross attempted to keep the aircraft flying (rather than letting it settle back to the ground) after a small hump in the runway caused the WB-47 to become airborne just below unstick airspeed. Failing to gain sufficient speed, the aircraft stalled, crashed, and burst into flames near the departure end of the runway. The pilots were able to blow the canopy and escape over the wing, albeit with serious burns. Maj Leinhart, Capt Hillis, and TSgt Heckman did not get out, and perished in the fire. As a side note, Frank Ross went on to command the 54th WRS in 1974-75. Please check out our Gone But Not Forgotten tribute to all the men who died supporting weather reconnaissance and atmospheric sampling in AWS aircraft. |

|

|

| Official

USAF Photos, Courtesy of Air Force Weather History Office |

|

| Two views of

51-2420 at Lajes AB after crash landing |

|

| 51-2420 / 10 Nov 1963 / 55th WRS /

Lajes AB, Azores On a trans-Atlantic flight to Tripoli, the crew of 2420 became lost due to a combination of crew error and mechanical failure. The N-1 compass had precessed, and this was not discovered in a timely manner. By then, the crew was way off course. Twice they were located and given DF steers to Lajes. By the time they arrived, their fuel state was critically low. On final, only the No. 1 and No. 4 engines were still producing power. The right wing struck the ground on landing. The copilot ejected at this time and was the only crew member injured. Departing the runway, the WB-47 skidded across the Lajes ramp, hitting a parked C-97. The B-47 aircraft suffered major structural damage and was salvaged in place. 51-2397 / 5 Dec 1966 / 53th WRS / Ramey, AFB Puerto Rico Aircraft crashed on landing at Ramey, no additional details available at this time. There were no serious injuries. 51-2366 / 20 Jun 1967 / 55th WRS / Clark AB, Philippines The crew and aircraft were TDY to Det 2, 57th WRS and flying ARCLIGHT missions. The forward main landing gear collapsed on landing. Thankfully, no one was injured, however the damage was beyond local repair capability. The 9th WRW decided to salvage the aircraft in place. 51-2373 / 26 Feb 1968 / 57th WRS / Hickam AFB, HI In 1975, when flying as a 1Lt instructor navigator out of the 55th WRS at McClellan, I had the opportunity to fly a WC-130 mission with Lt Col Richard K. "Snapper" McNab from the 9th WRW. As we waited to depart McClellan on a standard 2300L (0-Dark-Thirty to us MAC guys) Lark Uniform synoptic mission, McClellan tower cleared us to take the runway and hold for takeoff clearance. McNab declined, saying that he would stay short of the runway until takeoff clearance was given. Somewhere in the middle of the track, around 0400L, I asked him why he wouldn't hold on the runway. This was his story.... It turns out that back on that Feb night in 1968, Snapper was flying a local at Hickam. The night was very dark, with no moon. Returning to Hickam he requested, and was given, permission for a touch-and-go. On very short final, his landing lights shown on a Cessna sitting in the middle of the runway Snapper had been cleared to use. He pushed the throttles full forward and banked as much as possible (not much at his altitude) to try and clear the small aircraft. Unfortunately, it takes time to arrest a B-47 descent and begin to accelerate out. When they were safely in the climb, Snapper said to his copilot, "I think we missed him." "No, Sir.", came the reply, "The outrigger caught him right at the wing root." The B-47 had sheared off one wing of the Cessna, and left the lighter plane spinning in place. Snapper and the other pilot are still good friends 40 years later. It turns out that the tower had cleared the Cessna "On to Hold" and promptly forgot about him. The other pilot, a Honolulu doctor, said that those 6 J-47's at max power were by far the loudest noise he had ever heard. Neither one of them will ever take the active runway again without takeoff clearance in hand. The WB-47 suffered only very minor damage and continued in service until retirement Oct 1969. |

|

|

| Official

USAF Photo, via Col Sigmund Alexander |

|

|

| 51-2417 / Aug 1969 / 55th WRS /

McClellan AFB, CA Shortly after the AWS commander had announced the imminent demise of the WB-47 fleet, Maj Gary Clairmont and crew were returning to McClellan from a routine weather reconnaissance mission. When Maj Clairmont attempted to lower the landing gear, the forward main gear would not move out of the intermediate position. The crew followed all procedures, but the forward gear was stuck in this intermediate (partially down) position. Finally, Maj Clairmont decided to make a belly landing with all other gear in an up and locked position. The McClellan fire department foamed the runway, and Maj Clairmont made a perfect touchdown, keeping the WB-47 upright. Only "minor" sheet metal damage was incurred. The dedicated maintainers of the 55th jacked the WB-47 up and got the gear under her again. With extreme skill and cunning, all repairs were made using bench stock. Well, there was also a WC-135 "training" flight to Davis-Monthan to scavenge some B-47 belly panels. What might have been a major accident, was instead a minor blip. 51-2417 was made ready for her last flight to D-M, and an appointment to become razor blades along with her sister aircraft. General Jack Catton, Commander of MAC, sent congratulations to Maj Clairmont and crew for a job well done. The AWS, 9th WRW, and 55th commanders all echoed Gen Catton's sentiments. Thanks really need to go to all the ground support folks who kept the WB-47's flying. |

6. The End - and Thank You

for all of the Help

|

|

| Official

USAF Photo, Courtesy of Air Force Weather History Office |

|

|

| How Should the WB-47E be Remembered? The B-47 itself was truly ahead of its time. An entire generation of military and civilain aircraft can trace their roots to the Stratojet. Almost to a man, the pilots of the WB-47 remember it as a six engined fighter. The thin, highly swept, flexible wings made the aircraft amazingly nimble. From their perch high on the forward fuselage, the WB-47 pilots/weather observers had an unobstructed view in all directions, making the WB-47 one of the best visual weather observation platforms ever. As an atmospheric sampler, the WB-47 was state of the art. The U-1 foil system for gathering particulate debris, and pressure platform for whole air samples, are essentially still in use 45 years later on the WC-135W Constant Phoenix aircraft. The WB-47 had the range to cover all of the areas targeted in the early 1960's. It could, and did, accomodate an SEO as 4th man on numerous sampling missions. These missions quietly (and unknown to the public) reassured the National Command Authority that the US intelligence system was fully aware of USSR nuclear testing status. On the other hand, the automated aspects of the AN/AMQ-19 MET system never lived up to the promise. From the beginning there were problems. First, the Air Force had difficulty providing the APN-42 absolute altimeter to Lockheed. This meant that a key piece of the horizontal data was missing on the early aircraft. The doppler navigation "computer" was the ASN-6. This was selected for both the WB-47 and later WC-135 because the MET systems had to have a latitude / longitude input. The ASN-6 was notoriously inaccurate and needed constant updates from the navigator. On the polar missions, a special "grid" system of coodinates was used. The ASN-6 had to be slewed from standard coodinates to this grid system. It could take over 20 minutes to do this, during which time any "automatic" observations were useless. The AMT-13 dropsondes had a high failure rate using the revolver-type dispenser. It would take years to make them more reliable, and even then they needed an onboard dropsonde operator to preflight each instument and verify that it was transmiting valid data. The solution to many of the shortcomings of the WB-47 would have been a larger crew, something not really possible.

Special thanks to Bill Moore for the

above illustration of the crew issue. While it

might have been nice to carry an SEO, dropsonde operator, crew chief,

pilot or nav instructor/evaluator, etc., on any mission, there simply

was no room. A 4th, and occasional 5th, man flew many missions,

but there were really only 3 primary stations with ejection

seats. And once the two pilots strapped on the jet, they were a

part of the airplane for the entire 6, 7, or even 8-hour flight.

The world of the late 1960's was starting to take notice of noisy, dirty, aircraft engines, like the J-47's of the WB-47E. These truly were 1940's technology. And it is never easy to operate the last of any weapon system. The supply issues become harder with each passing month. All things considered, the WB-47 was ready to be retired. But she did her job pretty darn well, and looked good doing it ... |

|

|

| Official USAF Photo, Courtesy of Air Force Weather History Office | |

|

Thank You All I want to apologize in advance for any errors in this article. Having not flown the WB-47E, I may misinterpret what I've been told. Any mistakes are strictly my fault. Please feel free to contact me with comments or suggested changes at: awra038@aol.com Several people made the article possible. I'd like to start with Col Sigmund Alexander, USAF (Ret) of the B-47 Stratojet Association. Alex has collected volumous material about the B-47 for his own self-published works, and was extremely generous to allow me to share some of the data he collected. Also, B-47 Stratojet Association members Dick Purdum, Don (Tiny) Malm, and Bill "Modzelewski" Moore provided stories and information, as did AWRA Board Member John Hug. I hope they will also help me make corrections. Grant Matsuoka, a former MET/ARE technician, and extreme aircraft buff, has been truly generous in sharing the efforts of his own research. I need to acknowledge the assistance of the Air Force Weather History Office at Offutt AFB, NE. I'm looking to hear from any WB-47E flyer, AWS or AFTAC, who would like to share stories about their time with the aircraft or mission. Before you ask, yes, I know I did not talk about the lone WB-47B. That is another story ...... |

Return to the Top of the Page